How Does It Work To Clone An Animal

Many organisms, including aspen trees, reproduce by cloning, often creating big groups of organisms with the same Deoxyribonucleic acid. I case depicted hither is quaking aspen.

Cloning is the process of producing individual organisms with identical or near identical DNA, either past natural or artificial means. In nature, some organisms produce clones through asexual reproduction. In the field of biotechnology, cloning is the procedure of creating cloned organisms (copies) of cells and of DNA fragments (molecular cloning).

Etymology [edit]

Coined by Herbert J. Webber, the term clone derives from the Ancient Greek word κλών ( klōn ), twig, which is the procedure whereby a new establish is created from a twig. In botany, the term lusus was used.[1] In horticulture, the spelling clon was used until the early twentieth century; the terminal east came into use to point the vowel is a "long o" instead of a "short o".[2] [3] Since the term entered the pop lexicon in a more general context, the spelling clone has been used exclusively.

Natural cloning [edit]

Cloning is a natural form of reproduction that has allowed life forms to spread for hundreds of millions of years. It is a reproduction method used by plants, fungi, and leaner, and is also the manner that clonal colonies reproduce themselves.[4] [5] Examples of these organisms include blueberry plants, Hazel trees, the Pando trees,[6] [7] the Kentucky coffeetree, Myrica, and the American sweetgum.

Molecular cloning [edit]

Molecular cloning refers to the process of making multiple molecules. Cloning is usually used to dilate DNA fragments containing whole genes, but it tin too be used to amplify whatever DNA sequence such as promoters, non-coding sequences and randomly fragmented DNA. It is used in a wide array of biological experiments and practical applications ranging from genetic fingerprinting to large scale poly peptide product. Occasionally, the term cloning is misleadingly used to refer to the identification of the chromosomal location of a gene associated with a particular phenotype of involvement, such every bit in positional cloning. In practise, localization of the cistron to a chromosome or genomic region does not necessarily enable one to isolate or amplify the relevant genomic sequence. To dilate any DNA sequence in a living organism, that sequence must be linked to an origin of replication, which is a sequence of Dna capable of directing the propagation of itself and any linked sequence. Even so, a number of other features are needed, and a diverseness of specialised cloning vectors (small piece of Dna into which a foreign DNA fragment tin exist inserted) exist that allow protein production, analogousness tagging, unmarried-stranded RNA or DNA production and a host of other molecular biology tools.

Cloning of any Dna fragment substantially involves four steps[8]

- fragmentation - breaking autonomously a strand of DNA

- ligation – gluing together pieces of DNA in a desired sequence

- transfection – inserting the newly formed pieces of Dna into cells

- screening/choice – selecting out the cells that were successfully transfected with the new Deoxyribonucleic acid

Although these steps are invariable among cloning procedures a number of alternative routes can exist selected; these are summarized equally a cloning strategy.

Initially, the Deoxyribonucleic acid of interest needs to exist isolated to provide a DNA segment of suitable size. Afterwards, a ligation procedure is used where the amplified fragment is inserted into a vector (slice of Dna). The vector (which is frequently circular) is linearised using brake enzymes, and incubated with the fragment of interest under advisable conditions with an enzyme chosen DNA ligase. Following ligation, the vector with the insert of interest is transfected into cells. A number of alternative techniques are bachelor, such as chemical sensitisation of cells, electroporation, optical injection and biolistics. Finally, the transfected cells are cultured. Equally the aforementioned procedures are of particularly low efficiency, in that location is a need to identify the cells that take been successfully transfected with the vector construct containing the desired insertion sequence in the required orientation. Mod cloning vectors include selectable antibody resistance markers, which allow only cells in which the vector has been transfected, to grow. Additionally, the cloning vectors may comprise colour choice markers, which provide blueish/white screening (alpha-factor complementation) on 10-gal medium. Nevertheless, these selection steps exercise not absolutely guarantee that the Deoxyribonucleic acid insert is present in the cells obtained. Further investigation of the resulting colonies must be required to confirm that cloning was successful. This may be accomplished by ways of PCR, brake fragment analysis and/or Dna sequencing.

Cell cloning [edit]

Cloning unicellular organisms [edit]

Cloning jail cell-line colonies using cloning rings

Cloning a cell means to derive a population of cells from a unmarried cell. In the example of unicellular organisms such as bacteria and yeast, this procedure is remarkably simple and substantially only requires the inoculation of the appropriate medium. Still, in the case of cell cultures from multi-cellular organisms, cell cloning is an arduous task equally these cells will not readily grow in standard media.

A useful tissue civilization technique used to clone distinct lineages of jail cell lines involves the employ of cloning rings (cylinders).[9] In this technique a single-cell suspension of cells that have been exposed to a mutagenic agent or drug used to drive option is plated at high dilution to create isolated colonies, each arising from a single and potentially clonal distinct cell. At an early growth stage when colonies consist of only a few cells, sterile polystyrene rings (cloning rings), which have been dipped in grease, are placed over an individual colony and a minor amount of trypsin is added. Cloned cells are collected from inside the ring and transferred to a new vessel for further growth.

Cloning stalk cells [edit]

Somatic-prison cell nuclear transfer, popularly known as SCNT, can also be used to create embryos for enquiry or therapeutic purposes. The most likely purpose for this is to produce embryos for utilise in stalk cell research. This procedure is besides called "enquiry cloning" or "therapeutic cloning". The goal is not to create cloned human beings (chosen "reproductive cloning"), only rather to harvest stem cells that tin be used to study man evolution and to potentially treat affliction. While a clonal human blastocyst has been created, stem prison cell lines are yet to exist isolated from a clonal source.[10]

Therapeutic cloning is achieved by creating embryonic stalk cells in the hopes of treating diseases such as diabetes and Alzheimer's. The process begins by removing the nucleus (containing the DNA) from an egg cell and inserting a nucleus from the adult prison cell to be cloned.[11] In the example of someone with Alzheimer'due south disease, the nucleus from a peel prison cell of that patient is placed into an empty egg. The reprogrammed cell begins to develop into an embryo considering the egg reacts with the transferred nucleus. The embryo will become genetically identical to the patient.[11] The embryo will then class a blastocyst which has the potential to grade/become whatever cell in the body.[12]

The reason why SCNT is used for cloning is because somatic cells tin can be easily acquired and cultured in the lab. This process can either add or delete specific genomes of subcontract animals. A primal point to think is that cloning is achieved when the oocyte maintains its normal functions and instead of using sperm and egg genomes to replicate, the donor's somatic cell nucleus is inserted into the oocyte.[13] The oocyte will react to the somatic jail cell nucleus, the same way information technology would to a sperm cell's nucleus.[13]

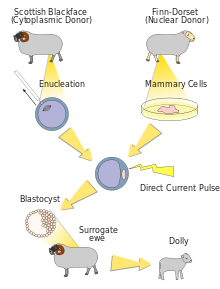

The process of cloning a particular farm animal using SCNT is relatively the same for all animals. The first step is to collect the somatic cells from the fauna that will exist cloned. The somatic cells could be used immediately or stored in the laboratory for later use.[13] The hardest role of SCNT is removing maternal Dna from an oocyte at metaphase II. Once this has been done, the somatic nucleus can be inserted into an egg cytoplasm.[thirteen] This creates a one-cell embryo. The grouped somatic jail cell and egg cytoplasm are then introduced to an electrical current.[13] This free energy will hopefully allow the cloned embryo to begin development. The successfully adult embryos are and then placed in surrogate recipients, such every bit a cow or sheep in the case of farm animals.[13]

SCNT is seen as a good method for producing agriculture animals for nutrient consumption. It successfully cloned sheep, cattle, goats, and pigs. Another do good is SCNT is seen as a solution to clone endangered species that are on the verge of going extinct.[13] However, stresses placed on both the egg cell and the introduced nucleus can be enormous, which led to a high loss in resulting cells in early inquiry. For example, the cloned sheep Dolly was born after 277 eggs were used for SCNT, which created 29 viable embryos. Only 3 of these embryos survived until birth, and only one survived to adulthood.[fourteen] Equally the procedure could non be automated, and had to be performed manually under a microscope, SCNT was very resource intensive. The biochemistry involved in reprogramming the differentiated somatic cell nucleus and activating the recipient egg was too far from existence well understood. However, by 2014 researchers were reporting cloning success rates of seven to eight out of x[15] and in 2016, a Korean Company Sooam Biotech was reported to be producing 500 cloned embryos per day.[sixteen]

In SCNT, non all of the donor cell's genetic information is transferred, as the donor prison cell's mitochondria that incorporate their ain mitochondrial DNA are left backside. The resulting hybrid cells retain those mitochondrial structures which originally belonged to the egg. As a event, clones such as Dolly that are born from SCNT are not perfect copies of the donor of the nucleus.

Organism cloning [edit]

Organism cloning (also chosen reproductive cloning) refers to the procedure of creating a new multicellular organism, genetically identical to another. In essence this form of cloning is an asexual method of reproduction, where fertilization or inter-gamete contact does not have identify. Asexual reproduction is a naturally occurring phenomenon in many species, including most plants and some insects. Scientists have fabricated some major achievements with cloning, including the asexual reproduction of sheep and cows. At that place is a lot of ethical debate over whether or not cloning should be used. However, cloning, or asexual propagation,[17] has been common practice in the horticultural world for hundreds of years.

Horticultural [edit]

Propagating plants from cuttings, such as grape vines, is an ancient form of cloning

The term clone is used in horticulture to refer to descendants of a single plant which were produced by vegetative reproduction or apomixis. Many horticultural plant cultivars are clones, having been derived from a single individual, multiplied by some process other than sexual reproduction.[18] As an example, some European cultivars of grapes represent clones that have been propagated for over two millennia. Other examples are potato and banana.[nineteen]

Grafting tin can be regarded equally cloning, since all the shoots and branches coming from the graft are genetically a clone of a single individual, but this particular kind of cloning has not come under ethical scrutiny and is generally treated as an entirely dissimilar kind of operation.

Many trees, shrubs, vines, ferns and other herbaceous perennials form clonal colonies naturally. Parts of an individual establish may go detached past fragmentation and grow on to become separate clonal individuals. A mutual case is in the vegetative reproduction of moss and liverwort gametophyte clones past means of gemmae. Some vascular plants eastward.g. dandelion and certain viviparous grasses also form seeds asexually, termed apomixis, resulting in clonal populations of genetically identical individuals.

Parthenogenesis [edit]

Clonal derivation exists in nature in some animal species and is referred to as parthenogenesis (reproduction of an organism by itself without a mate). This is an asexual form of reproduction that is simply plant in females of some insects, crustaceans, nematodes,[twenty] fish (for example the hammerhead shark[21]), and lizards including the Komodo dragon[21] and several whiptails. The growth and development occurs without fertilization by a male. In plants, parthenogenesis means the development of an embryo from an unfertilized egg cell, and is a component process of apomixis. In species that apply the XY sex-decision arrangement, the offspring will e'er be female. An example is the trivial burn pismire (Wasmannia auropunctata), which is native to Central and South America just has spread throughout many tropical environments.

Artificial cloning of organisms [edit]

Artificial cloning of organisms may likewise be called reproductive cloning.

First steps [edit]

Hans Spemann, a German embryologist was awarded a Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1935 for his discovery of the effect now known every bit embryonic induction, exercised by various parts of the embryo, that directs the evolution of groups of cells into particular tissues and organs. In 1924 he and his educatee, Hilde Mangold, were the first to perform somatic-cell nuclear transfer using amphibian embryos – one of the starting time steps towards cloning.[22]

Methods [edit]

Reproductive cloning by and large uses "somatic cell nuclear transfer" (SCNT) to create animals that are genetically identical. This process entails the transfer of a nucleus from a donor adult prison cell (somatic cell) to an egg from which the nucleus has been removed, or to a cell from a blastocyst from which the nucleus has been removed.[23] If the egg begins to divide unremarkably it is transferred into the uterus of the surrogate mother. Such clones are non strictly identical since the somatic cells may contain mutations in their nuclear Deoxyribonucleic acid. Additionally, the mitochondria in the cytoplasm besides contains Deoxyribonucleic acid and during SCNT this mitochondrial Dna is wholly from the cytoplasmic donor'southward egg, thus the mitochondrial genome is not the same equally that of the nucleus donor cell from which information technology was produced. This may have important implications for cantankerous-species nuclear transfer in which nuclear-mitochondrial incompatibilities may lead to death.

Artificial embryo splitting or embryo twinning, a technique that creates monozygotic twins from a single embryo, is not considered in the same mode equally other methods of cloning. During that procedure, a donor embryo is split in two distinct embryos, that can so be transferred via embryo transfer. It is optimally performed at the 6- to 8-prison cell stage, where information technology can be used equally an expansion of IVF to increase the number of available embryos.[24] If both embryos are successful, it gives rise to monozygotic (identical) twins.

Dolly the sheep [edit]

Dolly, a Finn-Dorset ewe, was the first mammal to accept been successfully cloned from an adult somatic cell. Dolly was formed past taking a cell from the udder of her vi-year-old biological mother.[25] Dolly's embryo was created past taking the prison cell and inserting it into a sheep ovum. Information technology took 435 attempts before an embryo was successful.[26] The embryo was then placed within a female sheep that went through a normal pregnancy.[27] She was cloned at the Roslin Institute in Scotland by British scientists Sir Ian Wilmut and Keith Campbell and lived at that place from her nativity in 1996 until her decease in 2003 when she was six. She was born on 5 July 1996 simply not announced to the world until 22 February 1997.[28] Her stuffed remains were placed at Edinburgh'south Royal Museum, part of the National Museums of Scotland.[29]

Dolly was publicly significant considering the endeavor showed that genetic material from a specific adult cell, designed to express simply a distinct subset of its genes, can exist redesigned to grow an entirely new organism. Before this demonstration, it had been shown past John Gurdon that nuclei from differentiated cells could give rise to an entire organism after transplantation into an enucleated egg.[30] However, this concept was not withal demonstrated in a mammalian arrangement.

The first mammalian cloning (resulting in Dolly) had a success rate of 29 embryos per 277 fertilized eggs, which produced three lambs at nascence, one of which lived. In a bovine experiment involving seventy cloned calves, one-third of the calves died quite young. The first successfully cloned equus caballus, Prometea, took 814 attempts. Notably, although the first[ clarification needed ] clones were frogs, no developed cloned frog has yet been produced from a somatic adult nucleus donor prison cell.

There were early claims that Dolly had pathologies resembling accelerated aging. Scientists speculated that Dolly's death in 2003 was related to the shortening of telomeres, DNA-protein complexes that protect the terminate of linear chromosomes. However, other researchers, including Ian Wilmut who led the team that successfully cloned Dolly, argue that Dolly's early death due to respiratory infection was unrelated to problems with the cloning process. This idea that the nuclei have not irreversibly aged was shown in 2013 to exist truthful for mice.[31]

Dolly was named after performer Dolly Parton considering the cells cloned to make her were from a mammary gland cell, and Parton is known for her ample cleavage.[32]

Species cloned [edit]

The mod cloning techniques involving nuclear transfer accept been successfully performed on several species. Notable experiments include:

- Tadpole: (1952) Robert Briggs and Thomas J. King had successfully cloned northern leopard frogs: thirty-five complete embryos and twenty-seven tadpoles from 1-hundred and four successful nuclear transfers.[33] [34]

- Carp: (1963) In China, embryologist Tong Dizhou produced the world'due south outset cloned fish by inserting the Dna from a cell of a male carp into an egg from a female person carp. He published the findings in a Chinese science journal.[35]

- Zebrafish: The showtime vertebrate cloned (1981) by George Streisinger (Streisinger, George; Walker, C.; Dower, North.; Knauber, D.; Singer, F. (1981), "Production of clones of homozygous diploid zebra fish (Brachydanio rerio)", Nature, 291 (5813): 293–296, Bibcode:1981Natur.291..293S, doi:10.1038/291293a0, PMID 7248006, S2CID 4323945 )

- Sheep: Marked the first mammal being cloned (1984) from early embryonic cells past Steen Willadsen. Megan and Morag[36] cloned from differentiated embryonic cells in June 1995 and Dolly from a somatic cell in 1996.[37] [35]

- Mice: (1986) A mouse was successfully cloned from an early embryonic cell. Soviet scientists Chaylakhyan, Veprencev, Sviridova, and Nikitin had the mouse "Masha" cloned. Research was published in the mag Biofizika book ХХХII, issue 5 of 1987.[ clarification needed ] [38] [39]

- Rhesus monkey: Tetra (January 2000) from embryo splitting and not nuclear transfer. More akin to artificial formation of twins.[40] [41]

- Grunter: the get-go cloned pigs (March 2000).[42] By 2014, BGI in China was producing 500 cloned pigs a year to exam new medicines.[43]

- Gaur: (2001) was the first endangered species cloned.[44]

- Cattle: Alpha and Beta (males, 2001) and (2005) Brazil[45]

- Cat: CopyCat "CC" (female, late 2001), Piffling Nicky, 2004, was the first cat cloned for commercial reasons[46]

- Rat: Ralph, the beginning cloned rat (2003)[47]

- Mule: Idaho Gem, a john mule born 4 May 2003, was the first horse-family clone.[48]

- Horse: Prometea, a Haflinger female born 28 May 2003, was the offset horse clone.[49]

- Canis familiaris: Snuppy, a male Afghan hound was the first cloned dog (2005).[l] In 2017, the world's offset gene-editing clone dog, Apple, was created by Sinogene Biotechnology.[51]

- Wolf: Snuwolf and Snuwolffy, the first two cloned female wolves (2005).[52]

- Water buffalo: Samrupa was the offset cloned water buffalo. It was born on 6 Feb 2009, at India's Karnal National Diary Research Plant but died 5 days after due to lung infection.[53]

- Pyrenean ibex (2009) was the first extinct animal to exist cloned back to life; the clone lived for vii minutes earlier dying of lung defects.[54] [55]

- Camel: (2009) Injaz, was the start cloned camel.[56]

- Pashmina goat: (2012) Noori, is the first cloned pashmina goat. Scientists at the kinesthesia of veterinary sciences and animal husbandry of Sher-e-Kashmir University of Agricultural Sciences and Engineering science of Kashmir successfully cloned the first Pashmina goat (Noori) using the avant-garde reproductive techniques nether the leadership of Riaz Ahmad Shah.[57]

- Goat: (2001) Scientists of Northwest A&F University successfully cloned the commencement goat which employ the adult female jail cell.[58]

- Gastric brooding frog: (2013) The gastric brooding frog, Rheobatrachus silus, thought to have been extinct since 1983 was cloned in Australia, although the embryos died after a few days.[59]

- Macaque monkey: (2017) Commencement successful cloning of a primate species using nuclear transfer, with the birth of 2 live clones named Zhong Zhong and Hua Hua. Conducted in China in 2017, and reported in Jan 2018.[60] [61] [62] [63] In Jan 2019, scientists in China reported the cosmos of v identical cloned cistron-edited monkeys, using the same cloning technique that was used with Zhong Zhong and Hua Hua and Dolly the sheep, and the gene-editing Crispr-Cas9 technique allegedly used by He Jiankui in creating the kickoff e'er factor-modified human babies Lulu and Nana. The monkey clones were made to study several medical diseases.[64] [65]

- Black-footed ferret: (2020) In 2020, a team of scientists cloned a female named Willa, who died in the mid-1980s and left no living descendants. Her clone, a female named Elizabeth Ann, was born on December ten. Scientists hope that the contribution of this individual will alleviate the effects of inbreeding and help black-footed ferrets meliorate cope with plague. Experts estimate that this female's genome contains 3 times as much genetic diversity every bit any of the modern black-footed ferrets.[66]

Homo cloning [edit]

Human cloning is the creation of a genetically identical re-create of a human. The term is more often than not used to refer to artificial homo cloning, which is the reproduction of homo cells and tissues. It does not refer to the natural conception and delivery of identical twins. The possibility of human cloning has raised controversies. These ethical concerns have prompted several nations to pass legislation regarding human being cloning and its legality. Every bit of right at present, scientists have no intention of trying to clone people and they believe their results should spark a wider discussion nearly the laws and regulations the world needs to regulate cloning.[67]

Two usually discussed types of theoretical human cloning are therapeutic cloning and reproductive cloning. Therapeutic cloning would involve cloning cells from a human being for use in medicine and transplants, and is an agile area of research, but is not in medical do anywhere in the world, equally of 2021[update]. Two common methods of therapeutic cloning that are being researched are somatic-cell nuclear transfer and, more recently, pluripotent stem jail cell consecration. Reproductive cloning would involve making an entire cloned human, instead of just specific cells or tissues.[68]

Ethical issues of cloning [edit]

There are a diverseness of ethical positions regarding the possibilities of cloning, particularly human being cloning. While many of these views are religious in origin, the questions raised by cloning are faced by secular perspectives as well. Perspectives on human cloning are theoretical, every bit human therapeutic and reproductive cloning are not commercially used; animals are currently cloned in laboratories and in livestock production.

Advocates support development of therapeutic cloning to generate tissues and whole organs to care for patients who otherwise cannot obtain transplants,[69] to avoid the need for immunosuppressive drugs,[68] and to stave off the effects of aging.[seventy] Advocates for reproductive cloning believe that parents who cannot otherwise procreate should have admission to the engineering science.[71]

Opponents of cloning take concerns that technology is not yet adult enough to be safe[72] and that it could be prone to abuse (leading to the generation of humans from whom organs and tissues would exist harvested),[73] [74] equally well as concerns about how cloned individuals could integrate with families and with society at large.[75] [76]

Religious groups are divided, with some opposing the technology as usurping "God's identify" and, to the extent embryos are used, destroying a human life; others support therapeutic cloning's potential life-saving benefits.[77] [78]

Cloning of animals is opposed past animal-groups due to the number of cloned animals that suffer from malformations earlier they die, and while food from cloned animals has been approved by the US FDA,[79] [fourscore] its apply is opposed past groups concerned nigh food safety.[81] [82]

Cloning extinct and endangered species [edit]

Cloning, or more precisely, the reconstruction of functional Dna from extinct species has, for decades, been a dream. Possible implications of this were dramatized in the 1984 novel Carnosaur and the 1990 novel Jurassic Park.[83] [84] The best current cloning techniques have an boilerplate success charge per unit of 9.4 percentage[85] (and every bit high as 25 percent[31]) when working with familiar species such every bit mice,[note 1] while cloning wild animals is usually less than ane percent successful.[88]

Several tissue banks take come into beingness, including the "Frozen zoo" at the San Diego Zoo, to store frozen tissue from the earth's rarest and near endangered species.[83] [89] [90] This is too referred to as "Conservation cloning".[91] [92]

In 2001, a cow named Bessie gave nascence to a cloned Asian gaur, an endangered species, but the dogie died after two days. In 2003, a banteng was successfully cloned, followed by iii African wildcats from a thawed frozen embryo. These successes provided hope that similar techniques (using surrogate mothers of another species) might be used to clone extinct species. Anticipating this possibility, tissue samples from the last bucardo (Pyrenean ibex) were frozen in liquid nitrogen immediately after it died in 2000. Researchers are also considering cloning endangered species such every bit the Giant panda and Cheetah.[93] [94] [95] [96]

In 2002, geneticists at the Australian Museum announced that they had replicated DNA of the thylacine (Tasmanian tiger), at the time extinct for about 65 years, using polymerase chain reaction.[97] Notwithstanding, on 15 February 2005 the museum appear that it was stopping the project after tests showed the specimens' Deoxyribonucleic acid had been also badly degraded by the (ethanol) preservative. On fifteen May 2005 information technology was appear that the thylacine project would be revived, with new participation from researchers in New South Wales and Victoria.[98]

In 2003, for the first time, an extinct animal, the Pyrenean ibex mentioned higher up was cloned, at the Centre of Food Technology and Research of Aragon, using the preserved frozen cell nucleus of the skin samples from 2001 and domestic caprine animal egg-cells. The ibex died shortly afterwards nascence due to physical defects in its lungs.[99]

I of the most predictable targets for cloning was in one case the woolly mammoth, but attempts to extract DNA from frozen mammoths have been unsuccessful, though a joint Russo-Japanese squad is currently working toward this goal.[ when? ] In January 2011, it was reported by Yomiuri Shimbun that a team of scientists headed by Akira Iritani of Kyoto University had congenital upon research by Dr. Wakayama, saying that they will extract Deoxyribonucleic acid from a mammoth carcass that had been preserved in a Russian laboratory and insert it into the egg cells of an Asian elephant in hopes of producing a mammoth embryo. The researchers said they hoped to produce a baby mammoth within six years.[100] [101] Information technology was noted, however that the result, if possible, would be an elephant-mammoth hybrid rather than a truthful mammoth.[102] Another problem is the survival of the reconstructed mammoth: ruminants rely on a symbiosis with specific microbiota in their stomachs for digestion.[102]

Scientists at the University of Newcastle and University of New South Wales announced in March 2013 that the very recently extinct gastric-brooding frog would be the subject field of a cloning endeavour to resurrect the species.[103]

Many such "De-extinction" projects are described in the Long At present Foundation's Revive and Restore Project.[104]

Lifespan [edit]

Afterwards an 8-year projection involving the use of a pioneering cloning technique, Japanese researchers created 25 generations of healthy cloned mice with normal lifespans, demonstrating that clones are not intrinsically shorter-lived than naturally born animals.[31] [105] Other sources accept noted that the offspring of clones tend to be healthier than the original clones and indistinguishable from animals produced naturally.[106]

Some posited that Dolly the sheep may have aged more speedily than naturally born animals, as she died relatively early for a sheep at the age of 6. Ultimately, her death was attributed to a respiratory illness, and the "avant-garde aging" theory is disputed.[107] [ dubious ]

A detailed study released in 2016 and less detailed studies past others suggest that once cloned animals get past the first month or two of life they are mostly healthy. Still, early on pregnancy loss and neonatal losses are yet greater with cloning than natural conception or assisted reproduction (IVF). Current research is attempting to overcome these bug.[32]

Sex as a reproductive strategy appears to be crucial for the continuity of life because of its essential function in maintaining the integrity and well-being of the genetic material of the germline.[108] Sexual reproduction leads to a kind of germline immortality past repairing (during meiosis) the genes of the egg and sperm cells so essential for the continuation of life over successive generations. The asexual process of cloning, in contrast, is deficient in Deoxyribonucleic acid repair processes (especially homologous recombinational repair) associated with meiosis. Far from beingness rejuvenating, commitment to clonal reproduction tin threaten the continuing evolutionary well being of genes, cells, organisms and even species.[108]

In popular culture [edit]

Word of cloning in the popular media frequently presents the subject negatively. In an article in the eight November 1993 article of Time, cloning was portrayed in a negative way, modifying Michelangelo'south Creation of Adam to depict Adam with five identical hands.[109] Newsweek 's 10 March 1997 outcome as well critiqued the ethics of human cloning, and included a graphic depicting identical babies in beakers.[110]

The concept of cloning, specially human being cloning, has featured a broad variety of science fiction works. An early fictional depiction of cloning is Bokanovsky's Process which features in Aldous Huxley'due south 1931 dystopian novel Brave New Earth. The process is practical to fertilized human eggs in vitro, causing them to split into identical genetic copies of the original.[111] [112] Post-obit renewed involvement in cloning in the 1950s, the field of study was explored further in works such as Poul Anderson's 1953 story UN-Man, which describes a technology called "exogenesis", and Gordon Rattray Taylor's book The Biological Time Bomb, which popularised the term "cloning" in 1963.[113]

Cloning is a recurring theme in a number of contemporary science fiction films, ranging from action films such equally Anna to the Infinite Power, The Boys from Brazil, Jurassic Park (1993), Conflicting Resurrection (1997), The 6th Day (2000), Resident Evil (2002), Star Wars: Episode Ii – Attack of the Clones (2002), The Island (2005) and Moon (2009) to comedies such every bit Woody Allen'south 1973 film Sleeper.[114]

The procedure of cloning is represented variously in fiction. Many works depict the bogus creation of humans by a method of growing cells from a tissue or DNA sample; the replication may be instantaneous, or accept place through slow growth of homo embryos in artificial wombs. In the long-running British television series Md Who, the Quaternary Md and his companion Leela were cloned in a thing of seconds from DNA samples ("The Invisible Enemy", 1977) and and then – in an apparent homage to the 1966 moving picture Fantastic Voyage – shrunk to microscopic size to enter the Md's body to combat an conflicting virus. The clones in this story are short-lived, and can simply survive a thing of minutes before they expire.[115] Scientific discipline fiction films such every bit The Matrix and Star Wars: Episode II – Assail of the Clones have featured scenes of human foetuses beingness cultured on an industrial scale in mechanical tanks.[116]

Cloning humans from body parts is also a mutual theme in scientific discipline fiction. Cloning features strongly among the science fiction conventions parodied in Woody Allen's Sleeper, the plot of which centres around an attempt to clone an assassinated dictator from his disembodied nose.[117] In the 2008 Doctor Who story "Journeying's End", a duplicate version of the Tenth Doctor spontaneously grows from his severed hand, which had been cut off in a sword fight during an before episode.[118]

The 2021 moving picture, Daughter Adjacent in which a adult female is adducted, drugged and brainwashed into condign obedient, living sexual practice doll. Later proving that she is a clone of a clone designed to assassinator the traffickers.

Afterward the death of her dearest 14-twelvemonth-old Coton de Tulear named Samantha in late 2017, Barbra Streisand announced that she had cloned the domestic dog, and was at present "waiting for [the two cloned pups] to get older so [she] can see if they have [Samantha's] chocolate-brown eyes and her seriousness".[119] The functioning price $fifty,000 through the pet cloning visitor ViaGen.[120]

Cloning and identity [edit]

Scientific discipline fiction has used cloning, most usually and specifically man cloning, to raise the controversial questions of identity.[121] [122] A Number is a 2002 play by English playwright Caryl Churchill which addresses the subject of man cloning and identity, especially nature and nurture. The story, prepare in the near future, is structured effectually the conflict between a male parent (Salter) and his sons (Bernard 1, Bernard 2, and Michael Black) – ii of whom are clones of the outset one. A Number was adapted by Caryl Churchill for television, in a co-production between the BBC and HBO Films.[123]

In 2012, a Japanese boob tube series named "Bunshin" was created. The story'due south main graphic symbol, Mariko, is a adult female studying kid welfare in Hokkaido. She grew upwardly always doubtful about the honey from her mother, who looked nada like her and who died nine years earlier. One 24-hour interval, she finds some of her mother'south belongings at a relative's house, and heads to Tokyo to seek out the truth behind her birth. She subsequently discovered that she was a clone.[124]

In the 2013 television series Orphan Black, cloning is used as a scientific report on the behavioral accommodation of the clones.[125] In a similar vein, the volume The Double past Nobel Prize winner José Saramago explores the emotional experience of a human being who discovers that he is a clone.[126]

Cloning equally resurrection [edit]

Cloning has been used in fiction as a way of recreating historical figures. In the 1976 Ira Levin novel The Boys from Brazil and its 1978 film adaptation, Josef Mengele uses cloning to create copies of Adolf Hitler.[127]

In Michael Crichton's 1990 novel Jurassic Park, which spawned a serial of Jurassic Park feature films, a bioengineering visitor develops a technique to resurrect extinct species of dinosaurs by creating cloned creatures using DNA extracted from fossils. The cloned dinosaurs are used to populate the Jurassic Park wildlife park for the amusement of visitors. The scheme goes disastrously wrong when the dinosaurs escape their enclosures. Despite being selectively cloned as females to forbid them from breeding, the dinosaurs develop the power to reproduce through parthenogenesis.[128]

Cloning for warfare [edit]

The use of cloning for military purposes has also been explored in several fictional works. In Medico Who, an conflicting race of armour-clad, warlike beings called Sontarans was introduced in the 1973 serial "The Time Warrior". Sontarans are depicted equally squat, baldheaded creatures who have been genetically engineered for combat. Their weak spot is a "probic vent", a small socket at the back of their neck which is associated with the cloning process.[129] The concept of cloned soldiers being bred for combat was revisited in "The Dr.'s Daughter" (2008), when the Doctor'due south DNA is used to create a female warrior chosen Jenny.[130]

The 1977 motion picture Star Wars was set against the backdrop of a historical disharmonize chosen the Clone Wars. The events of this war were not fully explored until the prequel films Set on of the Clones (2002) and Revenge of the Sith (2005), which describe a infinite war waged by a massive regular army of heavily armoured clone troopers that leads to the foundation of the Galactic Empire. Cloned soldiers are "manufactured" on an industrial scale, genetically conditioned for obedience and combat effectiveness. It is as well revealed that the popular character Boba Fett originated as a clone of Jango Fett, a mercenary who served equally the genetic template for the clone troopers.[131] [132]

Cloning for exploitation [edit]

A recurring sub-theme of cloning fiction is the use of clones as a supply of organs for transplantation. The 2005 Kazuo Ishiguro novel Never Let Me Go and the 2010 motion picture adaption[133] are prepare in an alternate history in which cloned humans are created for the sole purpose of providing organ donations to naturally born humans, despite the fact that they are fully sentient and self-aware. The 2005 film The Island [134] revolves around a similar plot, with the exception that the clones are unaware of the reason for their beingness.

The exploitation of human clones for unsafe and undesirable work was examined in the 2009 British science fiction flick Moon.[135] In the futuristic novel Cloud Atlas and subsequent film, ane of the story lines focuses on a genetically-engineered fabricant clone named Sonmi~451, i of millions raised in an bogus "wombtank", destined to serve from birth. She is one of thousands created for manual and emotional labor; Sonmi herself works equally a server in a restaurant. She later discovers that the sole source of food for clones, called 'Soap', is manufactured from the clones themselves.[136]

In the film Us, at some signal prior to the 1980s, the Usa Government creates clones of every citizen of the United States with the intention of using them to control their original counterparts, akin to voodoo dolls. This fails, as they were able to re-create bodies, merely unable to copy the souls of those they cloned. The project is abandoned and the clones are trapped exactly mirroring their in a higher place-ground counterparts' deportment for generations. In the present 24-hour interval, the clones launch a surprise attack and manage to complete a mass-genocide of their unaware counterparts.[137] [138]

In the series of A Certain Magical Index and A Certain Scientific Railgun, 1 of the espers, Mikoto Misaka, had DNA was harvested unknowingly, creating xx,000 exact but not equally powerful clones for an experiment. They were used as target practise by Accelerator, just to level upwards, as killing the original multiple times is incommunicable. The experiment ended when Toma Kamijo saved and foiled the experiment. The remaining clones have been dispersed everywhere in the world to conduct further experiments to expand their lifespans, save for at least 10 who remained in Academy City, and the concluding clone, who was not fully developed when the experiment stopped.

Run into also [edit]

- Frozen Ark

- The President's Council on Bioethics

Notes [edit]

- ^ 1 news article in 2014 reported success rates of 70-fourscore percent for cloning pigs past BGI, a Chinese company[86] and in another news article in 2015 a Korean Visitor, Sooam Biotech, claimed forty pct success rates with cloning dogs[87]

References [edit]

- ^ de Candolle, A. (1868). Laws of Botanical Nomenclature adopted by the International Botanical Congress held at Paris in August 1867; together with an Historical Introduction and Commentary past Alphonse de Candolle, Translated from the French. translated past H.A. Weddell. London: 50. Reeve and Co. : 21, 43

- ^ "Torrey Botanical Club: Volumes 42–45". Torreya. 42–45: 133. 1942.

- ^ American Association for the Advancement of Science (1903). Science. Moses King. pp. 502–. Retrieved eight Oct 2010.

- ^ "Tasmanian bush could be oldest living organism". Discovery Channel. Archived from the original on 23 July 2006. Retrieved 7 May 2008.

- ^ "Ibiza'due south Monster Marine Plant". Ibiza Spotlight. Archived from the original on 26 Dec 2007. Retrieved seven May 2008.

- ^ DeWoody, J.; Rowe, C.A.; Hipkins, V.D.; Mock, K.E. (2008). ""Pando" Lives: Molecular Genetic Evidence of a Behemothic Aspen Clone in Cardinal Utah". Western N American Naturalist. 68 (four): 493–497. doi:ten.3398/1527-0904-68.4.493. S2CID 59135424.

- ^ Mock, One thousand.East.; Rowe, C.A.; Hooten, G.B.; Dewoody, J.; Hipkins, V.D. (2008). "Blackwell Publishing Ltd Clonal dynamics in western North American aspen (Populus tremuloides)". U.S. Department of Agronomics, Oxford, UK : Blackwell Publishing Ltd. p. 17. Archived from the original on eleven August 2014. Retrieved v December 2013.

- ^ Peter J. Russel (2005). iGenetics: A Molecular Approach . San Francisco, California, United states of America: Pearson Education. ISBN978-0-8053-4665-7.

- ^ McFarland, Douglas (2000). "Preparation of pure cell cultures by cloning". Methods in Prison cell Science. 22 (1): 63–66. doi:10.1023/A:1009838416621. PMID 10650336.

- ^ Gil, Gideon (17 January 2008). "California biotech says it cloned a man embryo, but no stem cells produced". Boston Globe.

- ^ a b Halim, N. (September 2002). "All-encompassing new study shows abnormalities in cloned animals". Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Retrieved 31 October 2011.

- ^ Plus, M. (2011). "Fetal evolution". Nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 31 October 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f m Latham, K. E. (2005). "Early and delayed aspects of nuclear reprogramming during cloning" (PDF). Biological science of the Prison cell. pp. 97, 119–132. Archived from the original (PDF) on two August 2014.

- ^ Campbell KH, McWhir J, Ritchie WA, Wilmut I (March 1996). "Sheep cloned by nuclear transfer from a cultured cell line". Nature. 380 (6569): 64–6. Bibcode:1996Natur.380...64C. doi:10.1038/380064a0. PMID 8598906. S2CID 3529638.

- ^ Shukman, David (14 January 2014) Red china cloning on an 'industrial scale' BBC News Science and Environment, Retrieved x Apr 2014

- ^ Zastrow, Marker (8 February 2016). "Inside the cloning manufactory that creates 500 new animals a day". New Scientist . Retrieved 23 February 2016.

- ^ "Asexual Propagation". Aggie-horticulture.tamu.edu. Retrieved 4 Baronial 2010.

- ^ Sagers, Larry A. (2 March 2009) Proliferate favorite trees by grafting, cloning Archived 1 March 2014 at the Wayback Automobile Utah Stae University, Deseret News (Salt Lake Urban center) Retrieved 21 February 2014

- ^ Perrier, Ten.; De Langhe, Eastward.; Donohue, M.; Lentfer, C.; Vrydaghs, L.; Bakry, F.; Carreel, F.; Hippolyte, I.; Horry, J. -P.; Jenny, C.; Lebot, V.; Risterucci, A. -M.; Tomekpe, 1000.; Doutrelepont, H.; Ball, T.; Manwaring, J.; De Maret, P.; Denham, T. (2011). "Multidisciplinary perspectives on banana (Musa spp.) domestication". Proceedings of the National University of Sciences. 108 (28): 11311–11318. Bibcode:2011PNAS..10811311P. doi:10.1073/pnas.1102001108. PMC3136277. PMID 21730145.

- ^ Castagnone-Sereno P, et al. Diversity and evolution of root-knot nematodes, genus Meloidogyne: new insights from the genomic era Annu Rev Phytopathol. 2013;51:203-20

- ^ a b Shubin, Neil (24 Feb 2008). "Birds Do Information technology. Bees Do It. Dragons Don't Need To". The New York Times. Retrieved 21 February 2014

- ^ De Robertis, EM (April 2006). "Spemann's organizer and self-regulation in amphibian embryos". Nature Reviews. Molecular Cell Biological science. seven (4): 296–302. doi:10.1038/nrm1855. PMC2464568. PMID 16482093. . Encounter Box 1: Caption of the Spemann-Mangold experiment

- ^ "Cloning Fact Sheet". Human Genome Projection Information. Archived from the original on 2 May 2013. Retrieved 25 Oct 2011.

- ^ Illmensee K, Levanduski M, Vidali A, Husami N, Goudas VT (February 2009). "Human embryo twinning with applications in reproductive medicine". Fertil. Steril. 93 (ii): 423–7. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.12.098. PMID 19217091.

- ^ Rantala, Milgram, One thousand., Arthur (1999). Cloning: For and Against . Chicago, Illinois: Carus Publishing Visitor. p. 1. ISBN978-0-8126-9375-1.

- ^ Swedin, Eric. "Cloning". CredoReference . Retrieved 23 September 2013.

- ^ Lassen, J.; Gjerris, 1000.; Sandøe, P. (2005). "After Dolly—Ethical limits to the use of biotechnology on farm animals" (PDF). Theriogenology. 65 (5): 992–1004. doi:10.1016/j.theriogenology.2005.09.012. PMID 16253321.

- ^ Swedin, Eric. "Cloning". CredoReference. Science in the Contemporary World. Retrieved 23 September 2013.

- ^ TV documentary Visions of the Future part 2 shows this process, explores the social implicatins of cloning and contains footage of monoculture in livestock

- ^ Gurdon J (April 1962). "Adult frogs derived from the nuclei of single somatic cells". Dev. Biol. 4 (2): 256–73. doi:10.1016/0012-1606(62)90043-x. PMID 13903027.

- ^ a b c Wakayama Due south, Kohda T, Obokata H, Tokoro G, Li C, Terashita Y, Mizutani Eastward, Nguyen VT, Kishigami S, Ishino F, Wakayama T (vii March 2013). "Successful series recloning in the mouse over multiple generations". Cell Stalk Cell. 12 (3): 293–7. doi:10.1016/j.stem.2013.01.005. PMID 23472871.

- ^ a b BBC. 22 February 2008. BBC On This Day: 1997: Dolly the sheep is cloned

- ^ "ThinkQuest". Archived from the original on 23 October 2012. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ "Robert W. Briggs". National Academies Printing. Retrieved one Dec 2012.

- ^ a b "Bloodlines timeline". PBS.

- ^ "Gene Genie". BBC. 1 May 2000. Retrieved 4 August 2010.

- ^ McLaren A (2000). "Cloning: pathways to a pluripotent future". Science. 288 (5472): 1775–80. doi:10.1126/science.288.5472.1775. PMID 10877698. S2CID 44320353.

- ^ Chaylakhyan, Levon (1987). "Электростимулируемое слияние клеток в клеточной инженерии". Биофизика. ХХХII (5): 874–887. Archived from the original on eleven September 2016.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL condition unknown (link) - ^ "Кто изобрел клонирование?". Archived from the original on 23 Dec 2004. (Russian)

- ^ CNN. Researchers clone monkey by splitting embryo Archived 13 August 2006 at the Wayback Machine 13 January 2000. Retrieved 2008-08-05.

- ^ Dean Irvine (19 Nov 2007). "You, over again: Are nosotros getting closer to cloning humans?". CNN. Retrieved 4 August 2010.

- ^ Grisham, Julie (April 2000). "Pigs cloned for first time". Nature Biotechnology. 18 (4): 365. doi:x.1038/74335. PMID 10748477. S2CID 34996647.

- ^ Shukman, David (fourteen January 2014) Mainland china cloning on an 'industrial scale' BBC News Science and Environment, Retrieved 14 January 2014

- ^ "First cloned endangered species dies two days after nascency". CNN. 12 January 2001. Archived from the original on half-dozen June 2009. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- ^ Camacho, Keite. Embrapa clona raça de boi ameaçada de extinção Archived 21 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine. Agência Brasil. twenty May 2005. (Portuguese) Retrieved 5 August 2008

- ^ "Americas | Pet kitten cloned for Christmas". BBC News. 23 Dec 2004. Retrieved four August 2010.

- ^ "Rat called Ralph is latest clone". BBC News. 25 September 2003. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- ^ "Gordon Woods dies at 57; Veterinarian scientist helped create first cloned mule". Los Angeles Times. Associated Press. 25 August 2009. Retrieved four August 2010.

- ^ "World's kickoff cloned horse is built-in – 06 August 2003". New Scientist . Retrieved iv Baronial 2010.

- ^ "Commencement Dog Clone". National Geographic Society. Retrieved 4 August 2010.

- ^ "Chinese business firm clones gene-edited dog in bid to care for cardiovascular affliction". CNN. 27 Dec 2017. Retrieved 9 July 2020.

- ^ (1 September 2009) World's kickoff cloned wolf dies Phys.Org, Retrieved nine April 2015

- ^ Sinha, Kounteya (13 February 2009). "Republic of india clones world's kickoff buffalo". The Times of Bharat. Archived from the original on 11 August 2011. Retrieved iv August 2010.

- ^ Notation: The Pyrenean ibex is an extinct sub-species; the broader species, the Castilian ibex, is thriving. Peter Maas. Pyrenean Ibex – Capra pyrenaica pyrenaica Archived 27 June 2012 at the Wayback Motorcar at The Sixth Extinction]. Last updated xv April 2012.

- ^ "Extinct ibex is resurrected by cloning". The Daily Telegraph. 31 Jan 2009. Archived from the original on i February 2009.

- ^ Spencer, Richard (fourteen Apr 2009). "World'south get-go cloned camel unveiled in Dubai". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 15 Apr 2009.

- ^ Ishfaq-ul-Hassan (15 March 2012). "India gets its 2nd cloned creature Noorie, a pashmina goat". Daily News & Assay. Kashmir, India.

- ^ "家畜体细胞克隆技术取得重大突破 ——成年体细胞克隆山羊诞生".

- ^ Hickman, L. (18 March 2013). "Scientists clone extinct frog – Jurassic Park here nosotros come?". The Guardian . Retrieved 10 July 2016.

- ^ Liu, Zhen; et al. (24 January 2018). "Cloning of Macaque Monkeys by Somatic Jail cell Nuclear Transfer". Cell. 172 (4): 881–887.e7. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2018.01.020. PMID 29395327.

- ^ Normile, Dennis (24 January 2018). "These monkey twins are the outset primate clones made past the method that developed Dolly". Science. doi:ten.1126/scientific discipline.aat1066. Retrieved 24 Jan 2018.

- ^ Briggs, Helen (24 January 2018). "First monkey clones created in Chinese laboratory". BBC News . Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- ^ "Scientists Successfully Clone Monkeys; Are Humans Up Next?". The New York Times. Associated Press. 24 Jan 2018. Retrieved 24 Jan 2018.

- ^ Science China Press (23 January 2019). "Gene-edited disease monkeys cloned in Prc". EurekAlert! . Retrieved 24 January 2019.

- ^ Mandelbaum, Ryan F. (23 Jan 2019). "Mainland china's Latest Cloned-Monkey Experiment Is an Upstanding Mess". Gizmodo . Retrieved 24 January 2019.

- ^ "A black-footed ferret has been cloned, a get-go for a U.South. endangered species". Animals. 18 February 2021. Retrieved 20 February 2021.

- ^ Martinez, Bobby (26 Jan 2018). "Watch: Scientists clone monkeys using technique that created Dolly the sheep". Fox61. WTIC-Television. Retrieved 26 Jan 2018.

- ^ a b Kfoury, C (July 2007). "Therapeutic cloning: promises and issues". Mcgill J Med. x (two): 112–20. PMC2323472. PMID 18523539.

- ^ "Cloning Fact Sheet". U.S. Department of Energy Genome Program. 11 May 2009. Archived from the original on 2 May 2013.

- ^ de Grey, Aubrey; Rae, Michael (September 2007). Ending Aging: The Rejuvenation Breakthroughs that Could Reverse Human Aging in Our Lifetime. New York, NY: St. Martin's Printing, 416 pp. ISBN 0-312-36706-6.

- ^ Staff, Times Higher Education. x August 2001 In the news: Antinori and Zavos

- ^ "AAAS Statement on Human Cloning". Archived from the original on 11 September 2012. Retrieved half dozen June 2007.

- ^ McGee, Thou. (October 2011). "Primer on Ethics and Human Cloning". American Establish of Biological Sciences. Archived from the original on 23 February 2013.

- ^ "Universal Declaration on the Man Genome and Homo Rights". UNESCO. 11 November 1997. Retrieved 27 Feb 2008.

- ^ McGee, Glenn (2000). The Perfect Baby: Parenthood in the New World of Cloning and Genetics. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

- ^ Havstad JC (2010). "Human reproductive cloning: a conflict of liberties". Bioethics. 24 (2): 71–7. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8519.2008.00692.x. PMID 19076121. S2CID 40051820.

- ^ Bob Sullivan, Engineering science contributor for NBC News. November 262003 Religions reveal petty consensus on cloning – Wellness – Special Reports – Beyond Dolly: Human Cloning

- ^ Bainbridge, William Sims (October 2003). "Religious Opposition to Cloning". Journal of Evolution and Technology. 13.

- ^ Watanabe, S (September 2013). "Effect of calf death loss on cloned cattle herd derived from somatic cell nuclear transfer: clones with congenital defects would be removed past the death loss". Animal Science Periodical. 84 (ix): 631–8. doi:ten.1111/asj.12087. PMID 23829575.

- ^ "FDA says cloned animals are OK to eat". NBC News. Associated Press. 28 December 2006.

- ^ "An HSUS Report: Welfare Issues with Genetic Engineering and Cloning of Farm Animals" (PDF). Humane Club of the U.s..

- ^ Hansen, Michael (27 April 2007). "Comments of Consumers Union to The states Food and Drug Administration on Docket No. 2003N-0573, Draft Beast Cloning Gamble Assessment" (PDF). Consumers Union. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 December 2009. Retrieved sixteen Oct 2009.

- ^ a b Holt, W. V., Pickard, A. R., & Prather, R. S. (2004) Wildlife conservation and reproductive cloning. Reproduction, 126.

- ^ Ehrenfeld, David (2006). "Transgenics and Vertebrate Cloning every bit Tools for Species Conservation". Conservation Biological science. 20 (3): 723–732. doi:10.1111/j.1523-1739.2006.00399.x. PMID 16909565. S2CID 12798003.

- ^ Ono T, Li C, Mizutani E, Terashita Y, Yamagata Chiliad, Wakayama T (December 2010). "Inhibition of class IIb histone deacetylase significantly improves cloning efficiency in mice". Biol. Reprod. 83 (6): 929–37. doi:x.1095/biolreprod.110.085282. PMID 20686182.

- ^ Shukman, David (14 Jan 2014) China cloning on an 'industrial scale' BBC News Science and Environment, Retrieved 27 February 2016

- ^ Baer, Drake (8 September 2015). "This Korean lab has nearly perfected dog cloning, and that's merely the commencement". Tech Insider . Retrieved 27 February 2016.

- ^ Ferris Jabr for Scientific American. xi March 2013. Will cloning ever saved endangered species?

- ^ Heidi B. Perlman (viii October 2000). "Scientists Close on Extinct Cloning". The Washington Post. Associated Press. Archived from the original on viii July 2016. Retrieved 25 Baronial 2017.

- ^ Pence, Gregory E. (2005). Cloning Afterward Dolly: Who'southward However Afraid?. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN978-0-7425-3408-seven.

- ^ Marshall, Andrew (2000). "Cloning for conservation". Nature Biotechnology. 18 (11): 1129. doi:ten.1038/81057. PMID 11062403. S2CID 11078427.

- ^ "Conservation cloning".

- ^ "CNN.com – Nature – First cloned endangered species dies two days subsequently birth – January 12, 2001". edition.cnn.com . Retrieved 25 October 2020.

- ^ "Fresh effort to clone extinct animal". BBC News. 22 November 2013. Retrieved 25 October 2020.

- ^ "Endangered Species Cloning". world wide web.elements.nb.ca. Archived from the original on 21 September 2015. Retrieved 25 Oct 2020.

- ^ Khan, Firdos Alam (3 September 2018). Biotechnology Fundamentals. CRC Press. ISBN978-1-315-36239-7.

- ^ Holloway, Grant (28 May 2002). "Cloning to revive extinct species". CNN.

- ^ "Researchers revive programme to clone the Tassie tiger". The Sydney Morning time Herald. fifteen May 2005. Retrieved 1 February 2019.

- ^ Gray, Richard; Dobson, Roger (31 January 2009). "Extinct ibex is resurrected by cloning". The Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 1 February 2009. Retrieved ane Feb 2009.

- ^ "Scientists 'to clone mammoth'". BBC News. eighteen August 2003.

- ^ "BBC News". BBC. 7 December 2011. Retrieved nineteen August 2012.

- ^ a b "Когда вернутся мамонты" ("When the Mammoths Return"), 5 February 2015 (retrieved 6 September 2015)

- ^ Yong, Ed (15 March 2013). "Resurrecting the Extinct Frog with a Stomach for a Womb". National Geographic . Retrieved 15 March 2013.

- ^ "Long At present Foundation, Revive and Restore Project". 25 May 2017.

- ^ "Generations of Cloned Mice With Normal Lifespans Created: 25th Generation and Counting". Science Daily. 7 March 2013. Retrieved viii March 2013.

- ^ Carey, Nessa (2012). The Epigenetics Revolution. London, United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland: Icon Books Ltd. pp. 149–150. ISBN978-184831-347-7.

- ^ Burgstaller, Jörg Patrick; Brem, Gottfried (2017). "Aging of Cloned Animals: A Mini-Review". Gerontology. 63 (five): 419. doi:10.1159/000452444. ISSN 0304-324X. PMID 27820924.

- ^ a b Michod, Richard Due east. "What good is sex?" The Sciences, vol. 37, no. 5, September/October 1997, p. 42+

- ^ "Cloning Humans". Time. Vol. 142, no. 19. 8 November 1993. Archived from the original on five November 2017. Retrieved 5 November 2017.

- ^ "Today The Sheep ..." Newsweek. 9 March 1997. Retrieved 5 Nov 2017.

- ^ Huxley, Aldous; "Brave New World and Brave New World Revisited"; p. 19; HarperPerennial, 2005.

- ^ Bhelkar, Ratnakar D. (2009). Science Fiction: Fantasy and Reality. Atlantic Publishers & Dist. p. 58. ISBN9788126910366 . Retrieved 4 November 2017.

- ^ Stableford, Brian Chiliad. (2006). "Clone". Scientific discipline Fact and Science Fiction: An Encyclopedia. Taylor & Francis. pp. 91–92. ISBN9780415974608.

- ^ planktonrules (17 December 1973). "Sleeper (1973)". IMDb . Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ Muir, John Kenneth (2007). A Critical History of Physician Who on Television set. McFarland. pp. 258–9. ISBN9781476604541 . Retrieved 4 Nov 2017.

- ^ Mumford, James (2013). Ideals at the Beginning of Life: A Phenomenological Critique. OUP Oxford. p. 108. ISBN978-0199673964 . Retrieved vi Nov 2017.

- ^ Humber, James M.; Almeder, Robert (1998). Human Cloning. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 10. ISBN9781592592050 . Retrieved half-dozen November 2017.

- ^ Lewis, Courtland; Smithka, Paula (2010). "What's Continuity without Persistence?". Doctor Who and Philosophy: Bigger on the Within. Open Court. pp. 32–33. ISBN9780812697254 . Retrieved iv November 2017.

- ^ "Twice as nice: Barbra Streisand cloned her love domestic dog and has ii new pups". CBC News . Retrieved one March 2018.

- ^ Streisand, Barbra (2 March 2018). "Barbra Streisand Explains: Why I Cloned My Dog". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on i January 2022. Retrieved 23 June 2020.

- ^ Hopkins, Patrick (1998). "How Popular media represent cloning as an ethical problem" (PDF). The Hastings Centre Report. 28 (ii): 6–13. doi:x.2307/3527566. JSTOR 3527566. PMID 9589288. [ permanent expressionless link ]

- ^ "Yvonne A. De La Cruz Science Fiction Storytelling and Identity: Seeing the Homo Through Android Eyes" (PDF) . Retrieved 19 August 2012.

- ^ "Uma Thurman, Rhys Ifans and Tom Wilkinson star in two plays for BBC Two" (Press release). BBC. nineteen June 2008. Retrieved 9 September 2008.

- ^ "Review of Bunshin". nine June 2012.

- ^ foreverbounds. "Orphan Black (Telly Series 2013– )". IMDb . Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ Banville, John (10 October 2004). "'The Double': The Tears of a Clone". The New York Times . Retrieved xiv January 2015.

- ^ Christian Lee Pyle (CLPyle) (12 October 1978). "The Boys from Brazil (1978)". IMDb . Retrieved iii May 2015.

- ^ Cohen, Daniel (2002). Cloning. Millbrook Press. ISBN9780761328025 . Retrieved iv November 2017.

- ^ Thompson, Dave (2013). Doctor Who FAQ: All That's Left to Know About the Most Famous Fourth dimension Lord in the Universe. Hal Leonard Corporation. ISBN9781480342958 . Retrieved 4 Nov 2017.

- ^ Barr, Jason; Mustachio, Camille D. G. (2014). The Language of Medico Who: From Shakespeare to Alien Tongues. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 219. ISBN9781442234819 . Retrieved 5 November 2017.

- ^ McDonald, Paul F. (2013). "The Clones". The Star Wars Heresies: Interpreting the Themes, Symbols and Philosophies of Episodes I, Ii and Iii. McFarland. pp. 167–171. ISBN9780786471812 . Retrieved 4 Nov 2017.

- ^ compel_bast (15 Baronial 2008). "Star Wars: The Clone Wars (2008)". IMDb . Retrieved iii May 2015.

- ^ espenshade55 (11 February 2011). "Never Allow Me Go (2010)". IMDb . Retrieved three May 2015.

- ^ "The Island (2005)". IMDb. 22 July 2005. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ larry-411 (17 July 2009). "Moon (2009)". IMDb . Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ "Technology News – 2017 Innovations and Future Tech". Archived from the original on five January 2014. Retrieved 15 December 2013.

- ^ Daniel Kurland (23 May 2019). "United states of america: Who Are the Tethered?". Retrieved 11 July 2019.

- ^ Jason Spiegel (23 March 2019). "'Usa' Ending Explained: Could There Be A Sequel?". The Hollywood Reporter . Retrieved 11 July 2019.

Farther reading [edit]

- Guo, Owen. "World's Biggest Animal Cloning Eye Ready for 'xvi in a Skeptical China". The New York Times, 26 November 2015

- Lerner, K. Lee. "Creature cloning". The Gale Encyclopedia of Scientific discipline, edited past K. Lee Lerner and Brenda Wilmoth Lerner, 5th ed., Gale, 2014. Science in Context, link [ permanent expressionless link ]

- Dutchen, Stephanie (July 11, 2018). "Rise of the Clones". Harvard Medical Schoolhouse.

External links [edit]

| | Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cloning. |

- "Cloning". Cyberspace Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Cloning Fact Sheet from Man Genome Projection Information website.

- 'Cloning' Freeview video by the Vega Scientific discipline Trust and the BBC/OU

- Cloning in Focus, an attainable and comprehensive look at cloning inquiry from the University of Utah's Genetic Scientific discipline Learning Center

- Click and Clone. Endeavour it yourself in the virtual mouse cloning laboratory, from the University of Utah's Genetic Science Learning Center

- "Cloning Annex: A statement on the cloning written report problems by the President's Council on Bioethics" Archived 8 Jan 2009 at the Wayback Auto. National Review, 15 July 2002 8:45 am

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cloning

Posted by: wagnerolunnime1968.blogspot.com

0 Response to "How Does It Work To Clone An Animal"

Post a Comment